I spent some time last week in a concerted effort to examine the site of the 1970 London Road/Wilshire Heights landslide. (It took me five years to return to this haunted scene!) The effort was fun, but I learned more at home than I did on site. Gather round the campfire and I’ll tell you the whole tale.

To start with, here’s the most visible sign of this notorious event: the missing side of Kitchener Court, a hard-to-get-to cul-de-sac just south of the LDS Temple parking lot. I took this shot through a chainlink fence as a lone crow cawed.

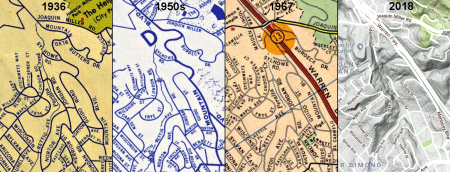

Deep in the night, the land on the left side, along with its houses, fell into the narrow headwater valley of Peralta Creek, where it pushed a row of recently built homes off their foundations down below on London Road. To orient ourselves, here’s a time series of road maps with London Road in the center. Click it to see its full 1300-pixel width.

Today the whole south end of London Road is gone, except for a tiny stub at the top of Maple Avenue. The north end, of later vintage, extends south from Maiden Lane. The 2018 map, from Google Maps with terrain visible, shows the topographic setting well.

Once upon a time London Road ran up a steep, secluded little wooded valley. It was platted in 1923 as part of the Wilshire Heights development and named for Jack London. It was built out by the late 1950s, after surges of homebuilding in the 1920s and 1940s. Meanwhile, East Bay MUD put water and sewer lines through, and Shell Oil emplaced a fuel pipeline down the valley to carry gasoline from its Martinez refinery to the Oakland Airport.

What could go wrong? A lot. Every steep headwater stream in the Oakland hills is prone to landslides. And this particular stream has carved its charming valley into the pulverized rock along the Hayward fault. Here’s what that shattered, highly weathered material — fault gouge — looks like where it’s exposed in the headscarp.

It was mid-February in 1962, on a dark and stormy night, when the combination of heavy rainfall and leakage from a broken water main caused the hillside just south of Maiden Lane to fail. Three homes were destroyed, never to be rebuilt.

Who knows how long the main had been leaking, or why. Slow landslides could have broken the main, or steady creep along the fault. Either would suffice, but probably both took part. On top of that, literally, was the added load on the hillslope from the new homes and their construction. No ordinances were in place at the time to ensure good construction practices on unstable slopes. And of course, for their landscaping, homeowners just added water. The land was probably in motion long before it finally slid.

Then came more construction in the 1960s: the Warren Freeway on one side, the LDS Temple complex on the other. People in the neighborhood said they noticed new ground movements during those years, but no cause-and-effect relationship can be confirmed this many years later. It is true, though, that when the Mormons sculpted the hilltop for their temple they disturbed an underground realm of water and soil. This photo shows groundwater coming up through the parking lot pavement, a phenomenon people described as the emergence of “hidden springs.”

But for the catastrophe that followed, the unregulated 1920s-era homebuilding on the bluffs of Kitchener Court was cause enough. During heavy rains in early January 1970, the whole east side of Kitchener Court began to collapse onto the south end of London Road. Within two weeks, some 40 houses were affected as 15 acres of land turned to hummocky ruin. The pipeline full of gasoline held, but Shell shut the whole thing down shortly thereafter. (In March 1969 it had been blown up, down in Redwood Canyon, engulfing the village of Canyon in a horrendous fire. Then this. And opposition continued to grow until the bad idea was safely dead.)

This land at the very end of Jordan Road is still iffy after almost 50 years.

There’s also the rock — you knew I’d get around to that. I don’t quite trust the geologic map in this area, but I can attest that serpentinite occurs here as it does in many places along California’s faults. These two specimens are good examples of our typical mixed serpentine rock and blueschist, and large boulders or outcrops of the same are visible in several places. There’s more on the west side of the temple. Serpentinite makes slide-prone ground, too, even when it’s not steep or waterlogged as this place was.

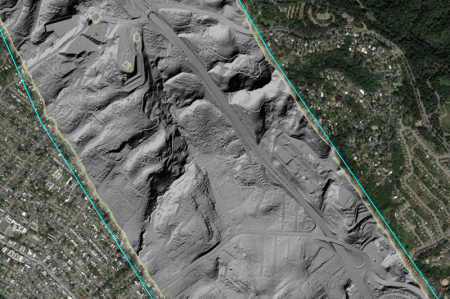

But on the whole, my poking around was frustrating because the land is so heavily overgrown and fenced off. Fortunately the US Geological Survey got funding for a lidar survey of the whole San Andreas fault system, including the Hayward fault, and the processed data — a digital elevation model or DEM, available from OpenTopography — is a fabulous resource for this exact area. After subtracting the vegetation and the structures from the data, the DEM becomes a grayscale image representing the bare ground, with the ghosts of streets and houses, here computer-illuminated from due northwest.

What’s handier, here’s the same with the Hayward fault superimposed. I usually have to do a lot of talking and armwaving to explain things, but not this time. Click in and wander around. The blue outline signifies a sag basin.

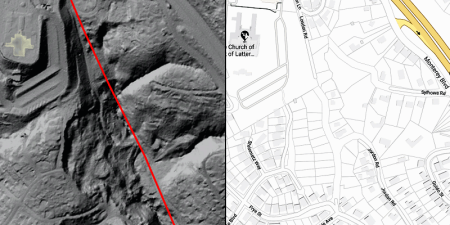

My final piece is this closeup of the slide area along with the lot lines and rights of way — more ghosts, still there after all these years.

There’s just one little house left on the east side of Kitchener Court, right up against the temple property. Incredible as it may seem, the adjoining lot, half fallen downhill with cliffs all around it, has a For Sale sign posted. Talk about a haunted place!

29 October 2018 at 9:10 am

Andrew – Your description and explanation of the London landslide are clear and fascinating. I am a geologist who grew up in the Fruitvale district in the 1950s and 1960s. I remember my mother bringing me to see the three houses destroyed by the landslide in 1962; I was 9-years old at the time. I’m amazed that I have no recollection of the 1970 landslide; I evidently had tunnel vision as a high-school senior focused on studies, college applications, and a weekend job.

I did my M.S. thesis in the Franciscan terrain between Livermore and Mount Hamilton in 1975, but I never studied the geology of the East Bay Hills in Oakland and Berkeley. I have not lived in California since 1976, but I visit the Bay Area every year or two. Your well illustrated posts help me to better understand the geology of districts and terrain which I remember well from childhood. Thank you!

29 October 2018 at 5:10 pm

The reason the road was named for Jack London is that some of the houses were built by Park Abbott, who was married to Joan London, Jack’s daughter. Park Abbott was a 1920s alum of Oakland High School and a co-founder of the old Co-Op supermarkets in Berkeley and beyond. He was interested in cooperative communities. The Abbott family had a chicken farm on the hilltop where the LDS temple was later built. Park Abbott liked to fly kites up there.

After the landslide, Professor Marshall Windmiller of SFSU was the president of the home owners’ association. They hired a detective to investigate the culpability of the LDS Church, but the church won in court.

There’s more to the story…I am working on it!

1 November 2018 at 7:18 pm

Amazing story! Excellent imagery, Andrew! Those LIDAR images make it jump right out.

5 November 2018 at 5:43 am

Really enjoyed reading this! One of my favorite walking areas, and always have been curious about its history.

16 November 2018 at 10:02 pm

I believe the Shell pipeline was replaced by at least one running from Chevron’s Richmond refinery to OAK along the Bay shore-and thus potentially at risk from liquefaction in the event of an earthquake.